Monday Jul 08, 2019

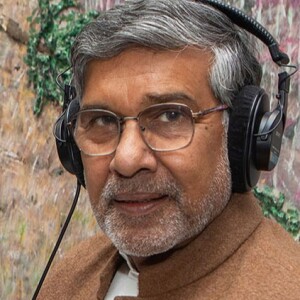

006 Kailash Satyarthi — fighting child labor from Delhi sweatshops to U.S. tobacco fields

Host Dr. Lee F. Ball, Appalachian's chief sustainability officer, interviews Nobel laureate Kailash Satyarthi. Satyarthi has spent 40 years freeing 80,000 children from slavery. Listen to his journey and his advice to App State students on the latest "Find Your Sustain Ability."

Transcript

Dr. Lee Ball: Kailash Satyarthi has spent his whole career saving the lives of children who are working as laborers around the world. Kailash was on our campus today, he actually flew over from Delhi, India, and he's leaving our campus to go straight to London, England. He was here today speaking and meeting students. He spoke to a full house in our Schaefer Center of over 1,000 people and had the opportunity to meet a lot of people. He stayed for a long time and shook hands and took pictures and people were extremely moved by his talk. Kailash was kind enough to stop by the studio. He had a lot to share about his organization and about the plight of child slaves and young laborers all around the world. There's a lot more information about Kailash's organization in our show notes. If you're interested in learning more, please check it out. We'll switch to his conversation now and I hope you enjoy.

L. Ball: Kailash Satyarthi, I want to thank you for coming here at Appalachian State. It's an honor to meet you and I welcome you to Boone, North Carolina.

Kailash Satyarthi: Thank you, Lee.

L. Ball: So for those who don't know, you've spent almost 40 years freeing over 80,000 children from slavery and unimaginable working conditions in India and around the world. You and your family and your colleagues have risked your lives countless times doing this work. You're like a modern day superhero.

K. Satyarthi: Not really.

L. Ball: Yeah. But unfortunately you can't solve these problems alone. I recognize that. There are over still 150 million children working in these conditions around the globe. My work here at the university with sustainability overlaps with yours because we cannot create a sustainable world on the backs of our children. So if we're going to ever find a way to create a sustainable future for the planet and its people, then we must end child slavery around the world that supports the desire for inexpensive goods, where the costs are externalized and subsidized by children. So because of your dedication to children around the world, you were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014. But first of all, congratulations, and thank you for this very important work. Secondly, has this attention of receiving the Nobel Peace Prize benefited your work trying to end child slavery around the world?

K. Satyarthi: Thank you, Lee, for this opportunity. First of all let me tell you that I am not a superhero. Superheroes can do the things on their own, but I always believed in togetherness, building coalitions, partnerships and mobilizing ordinary people for this sustainable change in the society to end child slavery and child labor. Though I had been working across the world, almost 150 countries for the last 20 years, with local partnerships and organizations to fight child slavery, we could not move much as I was expecting that people should recognize that it's serious evil that must end. It should have the political priority at local level and global level too. But after the Nobel Prize, it helped definitely. Because for the first time when the Nobel Peace Prize has been conferred to this cause through me. In their 100 years of history, they did not link the need of eradication of slavery and protecting children from it for a sustainable peace in the world.

K. Satyarthi: But they did it, so it was helpful. In fact, I kept fighting that this should be included in the Millennium Development Goals when they were being formulated in 1998, 99. In 2000, I did my best for the demand, organized some demonstrations and parallel meetings at the U.N., But it did not work. There was no mention of child labor or child slavery in MDGs. Then for sustainable development goals, I started the campaign globally, again with the help of many antislavery organizations and child rights groups. We collected millions of signatures and sent it to U.N. secretary-general and so on. In 2014 when I was spearheading this campaign, Nobel Peace Prize was announced. I did not miss this chance. I thought that I should meet the U.N. secretary-general and the governments of the world. Secretary-general was very pleased and convinced that this should be incorporated.

K. Satyarthi: My argument was that we cannot achieve most of the development goals without ending child labor. If, say 152, that time, 200 million children were working in child labor, we can never achieve the education for all goals. If 200 million children are working at the cost of adults' jobs, almost equal number of adults were jobless. Most of the times, these jobless adults were none but the very parents of these children. So my argument was clear that every child is working at the cost of one adult's job. So we cannot achieve that goal of reducing unemployment in the world. In 2014 when I met secretary-general, he was convinced and he suggested that it would be better to find some strong political champions, some presidents or prime ministers. So I immediately used this advice with none other than President Obama. I had a very good conversation with him.

K. Satyarthi: He was convinced and he said that, yes, I'm going to support it. He immediately agreed. So was the case of President Hollande of France and several other prime ministers and president and head of that nations and government. So I was able to gather strong support that child labor, child slavery, child trafficking, these issues should be the part of SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. And it happened. I succeeded in 2015. So in goal 8.7, all these things were included in the broader framework of the business solutions or employment generations, poverty elevations and so on. Now we have clear agenda and clear commitment for the eradication of child labor, slavery, trafficking. We also have a very clear goal for eradication of violence against children in all its forms, apart from ensuring good quality education for children and not only in primary but also in secondary schools and so many other things.

K. Satyarthi: So that was one of the significant successes after the Nobel Prize. But also in India, I have been able to ask the government and the government has changed the laws against child labor. They have also ratified the international conventions against child slavery and child labor. I fought for strong laws against child sexual abuse and rape of children in India and that was also successful. We worked with the governments in Sweden or in Germany and many other countries that they should increase or at least maintain their overseas development aid for education. That has been done. So in a way, it has given a very strong edge to advance my cause.

L. Ball: I'm very glad it happened for you and for all the children around the world. A lot of people here and around the world have no idea how many children are exploited. Children are in many cases treated worse than animals. I know that these are very complex issues. Can you explain how education has been playing a role in your work?

K. Satyarthi: Well, I have been advocating right from the beginning of my work in 1981 when I started. I learned even without any proper research or any study or evidences, but through the practice, through the practical work, I realized there is a very direct correlation between three things: child labor, poverty and illiteracy. This is a vicious triangle. We have to break it. Each of these things are cause and consequences of each other. If you continue child labor then the illiteracy will remain there. But if we are not able to ensure quality, free public education for every child, then the child labor will continue, at least in the poor countries and poor communities. So that has direct relations. Similarly, if the children remain child laborer and denied education, then they will remain poor for rest of their lives and their next generation will also remain poor and illiterate.

K. Satyarthi: That is intergenerational poverty and illiteracy through child labor. Slowly, people have started listening to that argument. Then we collected some evidences and some studies were done, and not by my organization only, but the World Bank, the UNESCO. ILO did such a studies and this relationship of triangular paradigm has been established. Now it's very clear that we cannot educate all children without eradication of child labor and we can not eradicate child labor without ensuring quality education for all children. There is a relation. We live in the world, which is basically the knowledge-driven world, or knowledge economy. We cannot think of sustainable economy growth in any country or poverty reduction or ending household poverty without an education and without knowledge today. But child labor is the biggest impediment in achieving this. So it is necessary that we have to invest both on education as well as on eradication of child labor.

K. Satyarthi: We are talking about 152 million children who are in full-time jobs. But we're also talking about 60 million children who have never seen the school doors, and another 200 million children dropped out from the schools because of the pull factor of child labor and also because of the pushback through poverty or other things, the family issues or social cultural issues and so on. That makes a vicious circle, that on one hand between 200 and 210 million adults are jobless in the world. One hundred and fifty-two million children are in full-time jobs and 260 million children who have to be in the schools in primary and secondary classes they are not there. That is the problem. There was one study done by World Bank and ILO that if you invest $1 on eradication of child labor, the return would be $7 over the next 20 years. So you can understand that it has a very strong economic imperative.

K. Satyarthi: Then the second thing is that if you invest on education for a child in developing country, then the return would be $15 over the next 20 years. So the best investment for economic growth and sustainability and poverty alleviation or justice, economic justice and equality in society is to invest in education. So that is the relation between all these factors.

L. Ball: So in addition to educating children in these impoverished areas, you also have a campaign, the 100 Million Campaign, did it focus on consumer education as well. Can you speak to that a little bit? Maybe give us an update on how it's going.

K. Satyarthi: Well, while working with children, youth, politicians, faith institutions, academicians in all my life, I have learned the power of youth should be channelized to solve this problem. That is largely untapped for this course. So my idea was that when 100 million, approximately, or a little more, 100 million young people are facing violence. That includes child labor, slavery, trafficking, child prostitution, use of children as child soldiers, or denial of education, health care. This is one scenario. On the other hand, hundreds of millions of young people are willing to take up challenges. They're ready to do something good for the society. So I thought that why can't at least 200 million young people should become the change makers for the lives of those 100 million young people who are deprived of childhood freedom, education, everything. So let 100 million youth should champion this cause.

K. Satyarthi: In this way, while I am addressing 200 million people, young people, simultaneously, 100 million who are deprived will get a strong voice from university students, college students and so on, well-off young people and children. On the other hand, those who are looking for some purpose and passion, those who wanted to prove themself, they could not find a space while studying in universities and their minds are sometimes narrowed down and their purposes and aims of lives have narrowed down for good scoring and better career and more learning and so on. Nothing is bad in it, but that it don't going to make this world a sustainable place. We can not save humanity. We can not save planet and people this way because if you make young people a tool or a lubricant or say part of a machine, this growth engine, then they will feel happy about it that they are the part of growth.

K. Satyarthi: But they do not remain human being with human soul. This is needed in this growth story. So this way, once they start thinking and working using the social media power, they can use internet, they can use other things to be the voices of other children, that will be good for them. They are also big consumers of most of the products which are made by child laborers and child slaves. So if the young people come to know that the shoes they're wearing or the shirt or chocolate they're eating, it is made by child slaves, I'm sure that they would be the first to change it and challenge it. Most of them, I'm not talking about all, but most of them will feel bad about it and they can use their power. So as conscious consumer they can make a difference for the sustainability of businesses and so on.

L. Ball: Child labor exists here in the United States. Can you describe what you know about this?

K. Satyarthi: Of course, I have been working on this issue in the United States for several decades, directly and indirectly through my partner organizations and so on. I know that how children are working not only in agriculture, the largest number of children, child laborers, in USA are engaged in agriculture sector, but also in sweatshops and sometimes the minor victims of trafficking and prostitution and so on. These things are not uncommon. There's a big fight. One of the issues which we ... many organizations and I have been fighting for is for a strong law to prohibit child labor in agriculture in USA. Because 20, 30 or 40 years ago, the agriculture work for children was not so dangerous because the use of pesticides and insecticides and machines and electricity was not so rampant, which is today is a serious problem. I've come across many examples where the young girls and boys are suffering diseases due to inhaling of those toxic chemicals. Sometimes, they are killed while working, operating a machine or electricity.

K. Satyarthi: That is an issue. Now we wanted to focus on one major area, and that is the employment of children in tobacco farms. It's an irony or one cannot give any argument that a young person is not allowed to smoke up to the age of 18, but a young person is allowed to work in tobacco fields at the age of 12 or 10 or 13, they're working in those situations. There is no justification for it. We wanted to focus on this through this 100 million campaign, that young people should raise this voice, that children must not be employed in any form, but to begin with, there should be complete revision of child labor in tobacco farming.

L. Ball: This is a big tobacco state, North Carolina, and especially in the eastern part of the state, there's a lot of tobacco still grown and it's a long history of children working in tobacco fields. In addition to educating children and their families and people around the world, what other strategies do you rely on that makes a difference in your work?

K. Satyarthi: Well, we have been fighting because we believe that investment in education through higher budget reallocation by the government is the key. That should also go with child-friendly education systems. So teachers training, investment on teachers, motivated teachers and so on. That should also be the part of it. So education is the key to many things, including development and social and economic justice, gender justice and poverty eradication. This is the strategy to ensure education ... investment in education for children. That requires social mobilization where people should demand that their children must be receiving good quality, free education, public education. That is also another reason.

L. Ball: Are there programs in place to educate families who are susceptible to the traffickers?

K. Satyarthi: Well, traffickers normally choose those areas which are less developed, uneducated families, deprived people, social deprivation also the part of the social cultural deprivation. For example, the entire Francophone Africa, the western African region, or some parts of South Asia or Southeast Asia, trafficking is quite rampant and in most cases, either the parents are not educated or the children do not have opportunity for education, so they are more susceptible for that. Only in few cases, in terms of the volume of trafficking in the world, some educated people are also lured away on false promises. They are shown some rosy dreams and told that their life would become like heaven and so on. So they are lured away like that and they don't know that they will end up in prostitution or forced labor.

L. Ball: Besides prosecution, what else is being done to prevent the factory owners from exploiting and abusing children?

K. Satyarthi: Well, I would say that child labor is an evil, social evil. It's a mindset issue. A lot of work has to be done to change the mindset of society, that people should feel their child labor is an evil, it causes poverty, it causes illness and it jeopardize education. So social awareness is needed to stop this as an evil. The second thing is it's the crime. So crime has to be dealt through law and order, through judiciary, through prosecution and conviction of the offenders. This is one part. That also requires the well oiled machinery for the prosecution, accountability in the entire system from the reporting to prosecution to conviction so it should reach to some conclusion. Then it is a development disaster. Until and unless we as society, international community, ensure basic things for the parents, social protection programs, permanent jobs, the minimum wages as prescribed under the law, these things are equally important.

K. Satyarthi: Then the accessibility to education. So schools have to be there in the villages and countrysides, teachers should be there in adequate numbers. Development factors play important role. Just the law or the prosecution won't work. The combination of all factors have to be there. So when I'm saying that it's a social awareness, it's equally important that the work has to be done in partnership with the companies. Those days are gone when we considered ... we meaning many of the civil society organizations, considered businesses and corporations as their enemy No. 1. They were culprits according to them. But this is not the case. Now the nature and character and role and power of corporate has changed and one should learn how to build mutual trust. The mutual trust between state, corporate and civil society is very much needed to solve this problem and many other problems in the world.

K. Satyarthi: So the corporations are not, in my opinion, just money making machines. They are also change-makers, knowingly or unknowingly. If they do it consciously for the betterment of people and planet, then they are the real change-maker for good. But if they just ignore those things, then it becomes disaster. But I see more and more corporations are coming forward, the industry leaders are coming forward to solve such problems. That is a good sign. This is also needed. So only prosecution won't work. The consumer should also feel responsible that instead of just calling for the boycott, they should demand certified and guaranteed quotes, which are free of child labor. The combination of these factors will definitely work.

L. Ball: Very holistic approach.

K. Satyarthi: Yeah, holistic approach.

L. Ball: Your wife's been by your side helping you all these years? First of all, how's she doing and how important has her support been to you?

K. Satyarthi: Oh, she has been a strong partner right from the beginning when nobody was convinced that I should give up my career as electrical engineer and I should embark upon this issue which was a nonissue in the minds of people. She was the only one who was convinced. Not only that, but she fought against it with all her efforts. She's good. She's fine. I spoke to her this morning and she was, enjoying with the group of children our Ashram. We had three rehabilitation come education and leadership building centers for the free child slaves and child labors. So she has been learning those centers for many, many years. Decades in fact. She is the mother of thousands of children who have gone through education and learning from those centers and also otherwise won't be freed from slavery. So that is good.

L. Ball: How many children are at the Ashrams at any given time?

K. Satyarthi: We have about 100 boys, 80, 90 to 100 normally and 30 girls in the girls center, 30, 35. Then we have another Ashram, Mukti Ashram, which is in outskirts of Delhi. That is used as the transit home. The children who are freed, they are brought over there and all the bureaucracy and legal work is done during that time. Then the repatriation, reintegration processes begin. Sometimes there are 150 children, 100 children. Even now there are about 100 children in the transit home, about 100 children in the long-term rehabilitation centers and 30 girls.

L. Ball: I can only imagine how stressful and emotional your work is. How do you take care of yourself and manage your work-life balance and make yourself more resilient?

K. Satyarthi: I don't see any distinction or difference in work and life. My personal life is my work and my work is my personal life. I can't recall that we could ... as family we could ever find some time for personal leisures or things like that, because we enjoy being with children, freeing children. That is much more rewarding than going to a leisure place for sightseeing and others. Once in a while we do, but it's hard.

L. Ball: Yeah. Well, you seem very happy. What message do you have for our students here at Appalachian State University?

K. Satyarthi: I enjoyed being with the young people today and also with little bit elderly people since yesterday and today both. They were filled with excitement and the emotions and energy. I could feel that energy inside the hall where I was speaking. I could tell that ... and that I normally say to many young people to transform into three D's, not that 3D cinema picture, but different kind of three D's. So my first D is, dream. If you're allowed to dream, dream big, dream bigger, dream biggest, dream as big as you can. If you are allowed to dream and you want to become a teacher, why don't you become the secretary of education? Why don't you become the vice chancellor or president of university? Dream big. So that's one. But those who dream for themselves and do not dream for others, for society and humanity, they never leave any footprint in the history.

K. Satyarthi: They cannot make the history. They are not shaped the history for the betterment. So dream big and dream for betterment. So that is one D. My second D is discover. Discover the inner power. Everybody is born with tremendous inner power. The power of greed, the power of resilience, the power of love, the power of compassion, the power of kindness, gratitude, all those powers should be ignited and used. Discover your inner power. Also discover opportunities outside. The world is full with opportunities, the world is full with beauty. We have to embrace that beauty of the world and positivity. That is my second D. The third D is, if you are able to dream, if you are able to discover then whom are you waiting for? Do. My third D is, do. Act now. Dream, discover and do.

L. Ball: Nice. Thank you very much. My last question: What inspires you and gives you hope to continue your work right now in this moment?

K. Satyarthi: My inspiration is my purpose and my purpose of life, my mission of life is very simple, that every child should be free to be a child. Every child should be free to laugh and cry and jump and play and make mistakes and learn and dream. So I have learned to celebrate every small success, to remain inspired. There is a reason to celebrate every day because the success ... there are successes smaller, bigger, medium. We should respect those successes. So even if one single child is freed, if one single child is enrolled in school, if one single child is passing out from a school through my effort, I feel the worth. That inspires me.

L. Ball: Kailash, thank you so much for coming today and coming all the way across the Atlantic Ocean. You came here from ...

K. Satyarthi: From India, from Delhi.

L. Ball: Oh, from Delhi!

K. Satyarthi: Yeah.

L. Ball: Then now you're going to London?

K. Satyarthi: Yeah.

L. Ball: So a few oceans. It's a real honor to have you here at the university and safe travels to you.

K. Satyarthi: Thank you. Thank you, Lee.

L. Ball: Thank you again for all of your work.

K. Satyarthi: Lovely. Thank you, Lee.